Today, I will discuss the threat intelligence process at a fictional but typical financial organization called DPS. The threat intelligence process is an integral component of securing and protecting DPS assets, brand, and reputation. The company must protect its proprietary intellectual property from numerous threats. At the same time, as a critical component of the financial system, DPS faces many attacks aimed at its data and processes. Finally, DPS must protect its brand and reputation, built upon customers’ trust in the company’s security. The threat intelligence process allows DPS to assimilate intelligence on indicators of compromise (IOC) and threat actors and take proactive steps to protect against, counter, or mitigate such threats.

The main challenges with the threat intelligence process include varied confidence levels in IOCs, ensuring actionable intelligence, timeliness of intelligence and response, and minimizing possible self-inflicted damage when responding. DPS receives IOCs from multiple sources, including paid services, vendors, open-source services, and governments. The quality of these intelligence feeds and the confidence in each source can vary widely. Further, intelligence sources may include IOCs that do not apply to DPS or are outdated. Finally, when responding to any possible threat, DPS must consider the possible impact that action may have on its business.

Current Symptoms and Concerns

The sheer volume of threat indicators strains DPS resources to filter through the noise and find credible, actionable threat indicators promptly. The primary concern is what we are not seeing. Intelligence analysts cannot devote enough time to vet every intelligence feed and indicator thoroughly. Poorly vetted indicators lead to many false positive alerts in the Security Operations Center (SOC). Security analysts who are inundated by what they believe are false positives may begin to ignore these alerts or create filters to whitelist the alerts.

Another symptom of the current process is that security analysts spend nearly all their time reacting to alerts. Many of these alerts are time-consuming and repetitive. Security analysts spend too much time gathering data, which decreases the time to discern and decide on a course of action (COA). Another manifestation of this issue is that security analysts do not have time to search and hunt deeper threats and vulnerabilities proactively. This lack of time to proactively search for threats and vulnerabilities increases the already considerable advantage the attackers enjoy.

Current human-centered cyber defense practices employed by DPS cannot keep pace with the speed and pace of the threats targeting organizations like DPS. Further, the speed of attack versus the speed of response gap is worsening. Defenders need to drastically increase the speed of both detection of and response to cyber-attacks. Organizations like DPS must automate many risk-based decisions to facilitate an increase in detection and response speed.

The Current Process

The current-state process is manual and error-prone. When intelligence feeds are received, the intelligence analysts must manually filter the IOCs to remove IOCs not applicable to the organization. This manual process can lead to two common errors. First, leaving non-applicable IOCs in the intelligence feed creates additional work for the SOC analysts. Second, accidentally removing applicable IOCs may lead to vulnerabilities or compromises not being discovered.

Once the intelligence analysts finish filtering the IOCs, the SOC analysts must retrieve and assimilate information from the applicable security devices to enrich the data. During this process, the SOC analysts must search the log records of the security devices for evidence of the IOCs. This critical step is highly dependent on the abilities and diligence of the SOC analysts. If SOC analysts overlook data sources or do not perform a comprehensive search, the SOC analysts may mistakenly determine that the IOC is a false positive. After gathering all the information, the SOC analysts review the information and determine the appropriate COA. The current-state process provides no feedback loop to inform the intelligence analysts of the quality of the intelligence feeds.

Feasibility of a Solution

DPS has many technical resources that it could use to improve the threat intelligence process. Recent advances in security automation and orchestration hold great promise and, if applied correctly, could improve both the quality and speed of the threat intelligence process. DPS can leverage the security and information resources at its disposal to increase the speed, accuracy, and applicability of intelligence feeds. By improving the threat intelligence intake, DPS may also automate much of the response action. The improvements and automation will allow humans to focus on discerning and deciding on appropriate COA.

The future threat intelligence business process must address the issues and concerns present in the existing process. The future process must leverage security automation and orchestration to enrich intelligence and automate many of the repetitive, error-prone tasks currently performed by security analysts. Using automation to enhance the process, security analysts can focus on decision-making and deeper threat-hunting activities.

The Future-State Process – Applying Automation

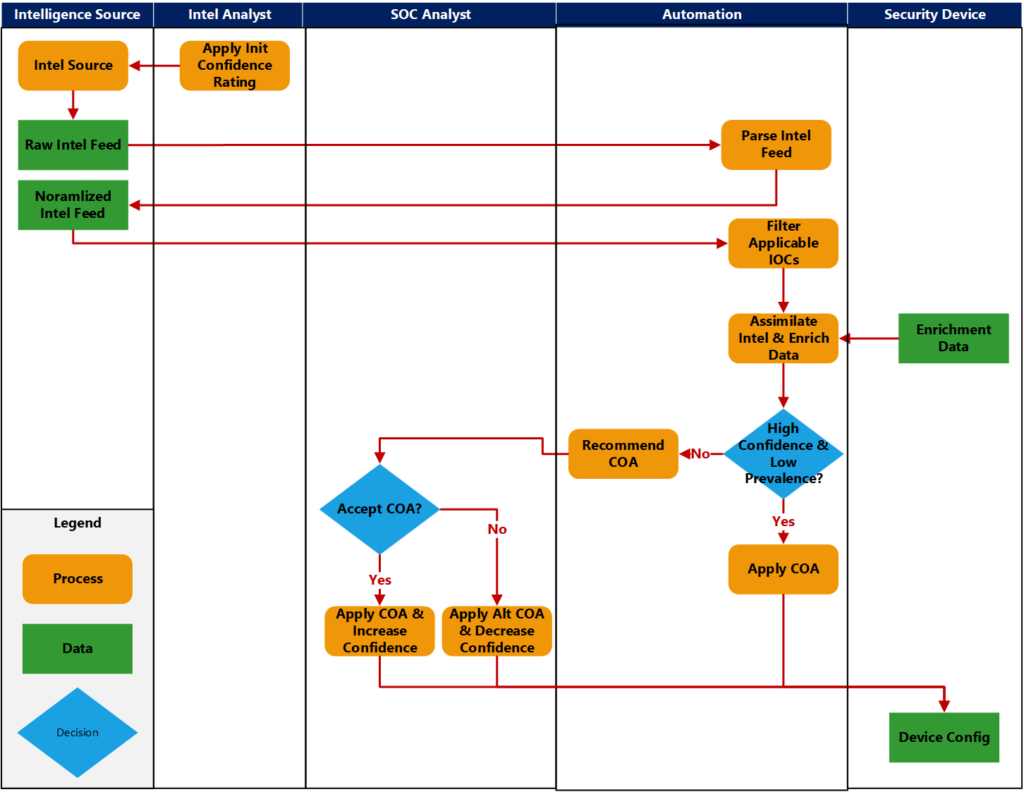

The future process (see Figure 1) will leverage security automation and orchestration to enrich intelligence and automate many of the repetitive, error-prone tasks currently performed by SOC analysts. Using automation in the threat intelligence process can increase confidence in intelligence feeds, decrease the time to detect, decrease the time to respond, and increase awareness of advanced threats. Also, by using automation to enhance the process, SOC analysts can focus on decision-making and deeper threat-hunting activities.

Intelligence analysts will evaluate and provide an initial confidence rating for each intelligence source. Then, the actions taken by SOC analysts can influence the confidence ratings, thus providing a feedback loop to the intelligence analysts. Automation can also quickly filter out non-applicable and outdated IOCs under the principle of when in doubt, keep it in. The feedback loop will help refine this process. Intelligence analysts must periodically reevaluate the confidence ratings and applicability of each of the threat intelligence feeds.

For each remaining IOC, automation can retrieve enrichment data from security devices and other data enrichment sources. The automation should enrich IOCs with prevalence (have we seen this in our environment), applicability (do we use the vulnerable product), confidence, and possible impact information (how many and what devices might be impacted).

Based on the enriched data, the automation will determine a recommended COA. For high-confidence, low-impact IOCs, the automation can apply the COA. For all other indicators, the automation can present the enriched data and the recommended COA to the SOC analyst. The SOC analyst can decide whether to apply the recommended COA or take alternate action. The confidence rating of the originating intelligence feed is boosted if the SOC analyst chooses the recommended COA. Otherwise, if the SOC analyst selects an alternate COA or determines the alert is a false-positive, the confidence rating is diminished.

Goals and Expected Benefits

There are two major benefits expected from the future-state process. The first benefit is increasing the speed of response and remediation of IOCs received from intelligence feeds. The other significant benefit is the more effective use of SOC analysts. With the future-state process, the SOC analysts can concentrate on events that require human decision-making and on proactive threat-hunting activities., The future-state process must focus on several key goals to achieve the expected benefits. These goals include:

- Improve the confidence ratings and consistency of intelligence feeds;

- Automate the enrichment of IOCs, which will decrease the time to detect, the time SOC analysts spend enriching alerts, and the time to respond;

- Fully automate the response for many IOCs, further reducing the time to respond; and

- Identification of the most-reliable intelligence sources and discontinuance of those sources that provide little value.

Meeting the above goals will ensure that the future-state process delivers the expected benefits. With SOC analysts spending more time on proactive measures, such as threat hunting, the security team will be able to detect more advanced threats and increase the security posture of the company. As a side benefit, the SOC analyst’s role will become more rewarding and allow for career growth, which should help the company retain quality analysts.

About the author: Dr. Donnie Wendt, DSc., is an information security professional focused on security automation, security research, and machine learning. Also, Donnie is an adjunct professor of cybersecurity at Utica University. Donnie earned a Doctorate in Computer Science from Colorado Technical University and an MS in Cybersecurity from Utica University.